Prabu Pathmanathan, 31, was the first Malaysian to be hanged in

Singapore since Mahathir’s government announced in September that it

would soon move to abolish the death penalty. Malaysia has installed a

moratorium on the punishment until then.

The administration, fresh off its election victory in May, has made human rights a key part of its policy agenda.

Capital punishment for serious crimes including murder and drug trafficking has been carried out in

Singapore and Malaysia since the days of British colonial rule.

In some severe cases, execution had been mandatory – meaning judges had no alternative sentence if the accused was found guilty.

But after a review in 2012, the city state granted judges more discretion.

Since the September announcement that

Malaysia would soon

move towards total abolition, activists in the country have said they would go all out to save the lives of Malaysians facing execution abroad.

Activist and lawyer N. Surendran, who represented Prabu’s family in

their eleventh-hour attempt to obtain clemency for the 31-year-old,

confirmed to the

South China Morning Post that the execution had taken place at dawn on Friday.

Surendran said Prabu’s family would cremate his remains later on Friday.

The

Post has requested a comment from Singapore’s home affairs ministry.

Prabu in 2014 was convicted of smuggling 227.82g of diamorphine – or heroin – into Singapore.

“The execution was an unlawful, and brutal act, carried out in breach

of due process and in defiance of the appeals made by neighbouring

Malaysia,” said Surendran, who told the

Post that several Malaysian cabinet members had spoken directly with Singaporean leaders in a failed bid to halt the execution.

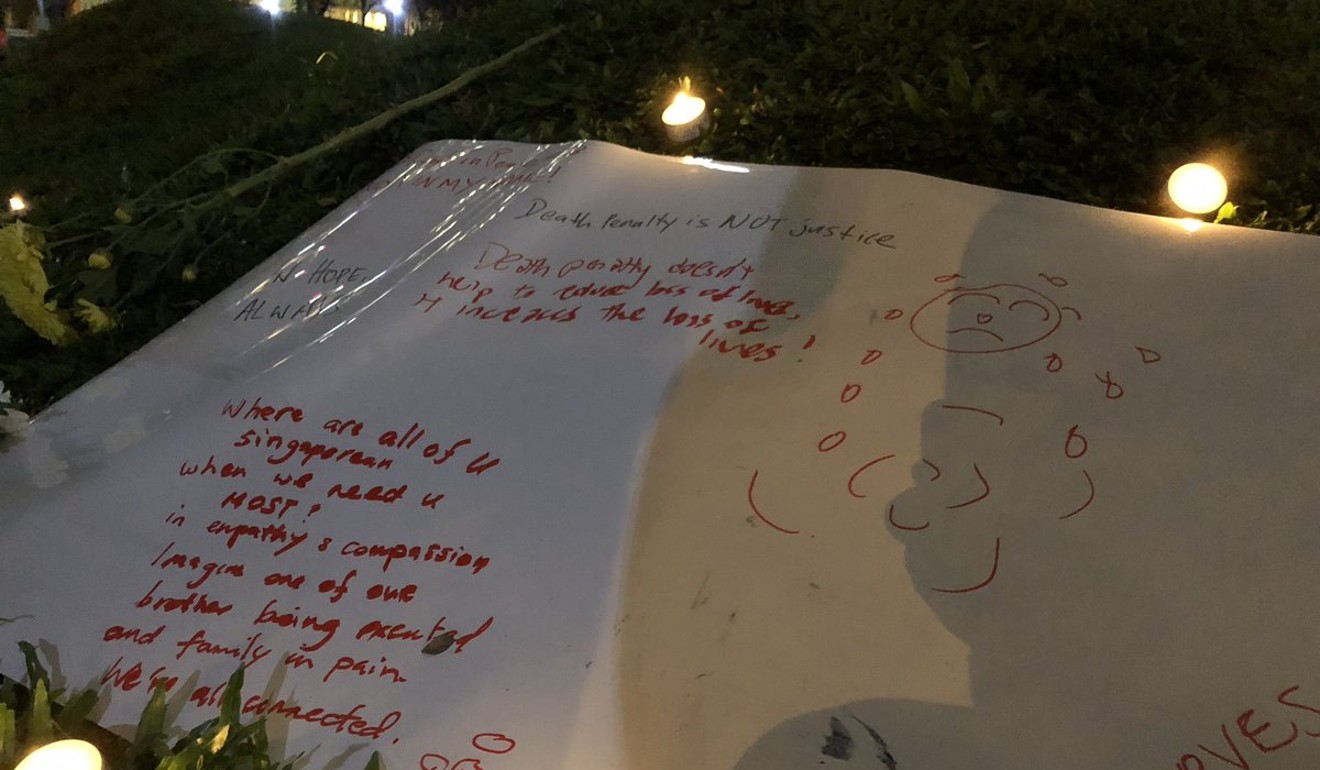

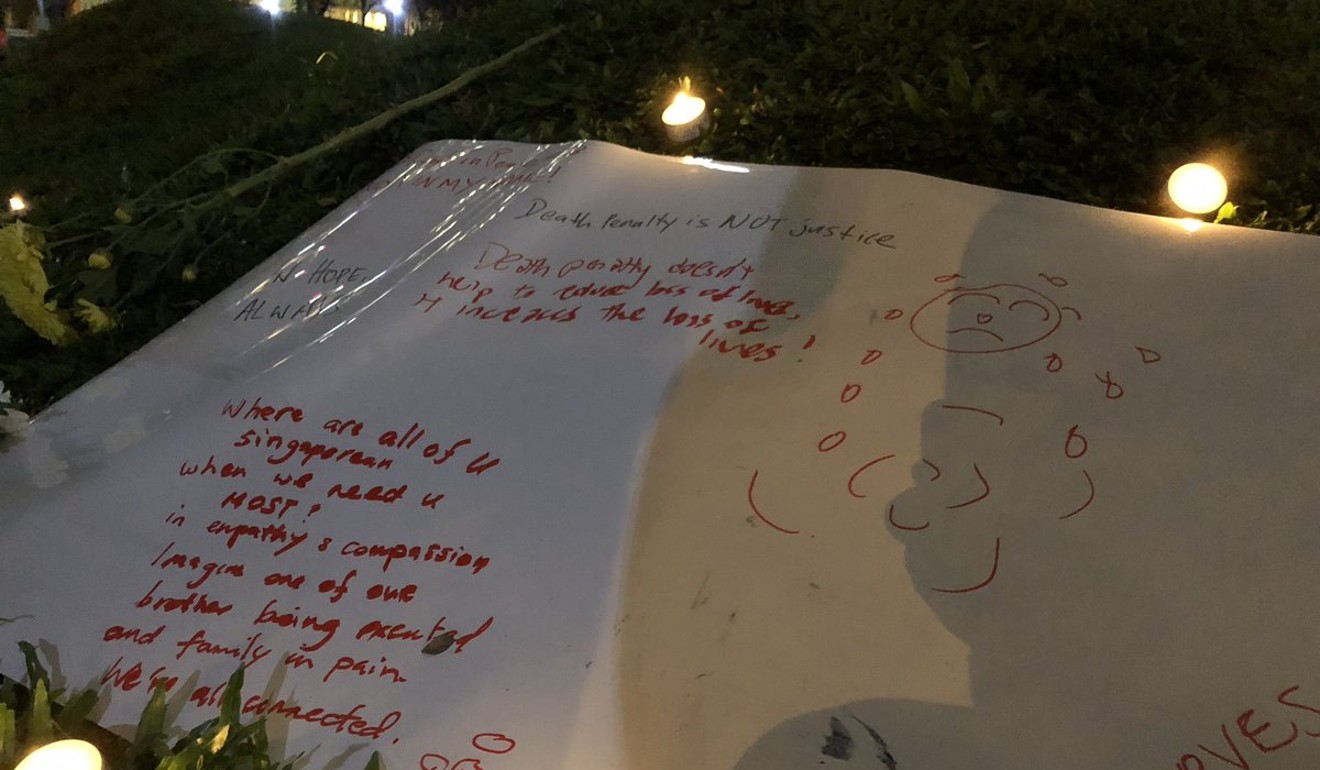

A vigil for Prabu. Photo: Kirsten Han

A vigil for Prabu. Photo: Kirsten Han

Malaysian de facto law minister Liew Vui Keong earlier told local

media he had written to the Singapore government, urging it to commute

Prabu’s death sentence.

When asked by local media what would happen if the execution was

carried out, he responded: “It will be a sad day, I hope they don’t do

it.”

Surendran said on Thursday evening the Singapore President’s Office

had delivered a letter to Prabu’s family in response to their petition,

stating that “the clemency process has concluded” and it was “unable to

accede to [their] request”.

The lawyer criticised this move – saying the decision to “reject the

family’s clemency petition without even considering it” was unlawful.

Anti-death penalty activists said there had been seven executions in October – four this week including Prabu.

The Singapore Prison Service does not routinely release information

about executions apart from figures released in its annual report.

The 2017 annual report showed eight people were executed in 2017, up from four in 2016.

“It seems that executions are increasing in Singapore. The sort of

discussion among the Malaysian government that’s taking place now is not

taking place here,” said Kirsten Han, a prominent Singaporean

anti-death penalty activist and journalist.

A band calling for an end to the death penalty performs in Singapore. Photo: AFP

A band calling for an end to the death penalty performs in Singapore. Photo: AFP

Said Han: “Singaporean society is told the death penalty keeps people

safe, that it’s a deterrent. This is the message that travels down from

leaders, but alternative deeper opinions are not aired.

“There have been studies that show when you explore the nuances,

support for the death penalty drops: the more you know about the death

penalty, the more likely you are to think twice.”

The Singapore government routinely pushes back against the country’s tiny but vocal anti-death penalty lobby.

Last year, law and home affairs minister K. Shanmugam slammed

activists for “romanticising individuals involved in the drug trade”.

The minister said capital punishment would remain part of Singapore’s

comprehensive anti-drug framework that includes rehabilitating abusers.

Speaking at the Asia-Pacific Forum Against Drugs, Shanmugam said: “I

have said repeatedly, [we] do not take any joy or comfort in having the

death penalty, and nobody hopes or wants to have it imposed.

“We do it reluctantly, on the basis that it is for the greater good

of society … it saves more lives. That is the rationale on which we have

it.”

Globally, 106 countries have abolished the death penalty and 142 in total are abolitionist in law or practice.

No comments:

Post a Comment